#11 Dr. Jos Delbeke - EU ETS: Two Decades of Europe’s Carbon Market — Key Turning Points, Challenges and Policy Lessons

This is the transcript of my episode with Dr. Jos Delbeke. In this conversation, we trace how the EU Emissions Trading System grew from a clean economic idea into a robust market that cut emissions, survived crises, and now targets hard-to-abate industry. Dr. Jos Delbeke shares inside lessons on how it started, the importance of measurement, allocation and price design, the evolution from low to high prices, and the road ahead with CBAM and ETS2.

Timestamps:

6:55 - Getting Started in 2005: MRV And Sector Choices

12:14 - How The Initial Carbon Price Quickly Made an Impact

16:02 - Allocation Rules and Changes over Time

24:44 - The Collapse of EU ETS Prices - Financial crisis and Carbon Credits

28:28 - Solutions by the EU Commission to Stabilise Prices

32:41 -Key Lesson: The importance of having a good governance system

36:10 - Future Challenges and opportunities for the EU ETS

If you have any advice on how to improve the podcast or advice on future guests or episodes or ideas, please let me know. I’d love to hear from you.

The History, Challenges & Future of the EU ETS

Arvid Viaene:

On paper, climate policy sounds simple: you put a price on carbon. Either you tax it, or you cap it and let firms trade. In practice, doing that for one of the world’s biggest economies — as the first mover — is anything but simple.

This episode looks at 20 years of the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS): how it started, where it nearly failed, how it recovered, and where it’s going next. The ETS is the world’s first major carbon market, and it has helped drive CO₂ emissions in covered sectors down by more than 50% since 2005.

My guest is Professor Jos Delbeke. Jos is the former Director-General for Climate Action at the European Commission and one of the key architects of the EU ETS. He now holds the EIB Chair on Climate Policy and International Carbon Markets and served as the Commission’s lead climate negotiator in the run-up to the Paris Agreement.

By the end of this conversation, you’ll be able to answer three big questions:

Why did the EU choose cap-and-trade instead of a carbon tax?

Why were carbon prices so low for so long — and what did the Commission do to fix that?

Where is the ETS going now, as it expands to new sectors and pushes industry to decarbonize?

Jos Delbeke: My pleasure to be with you today.

Arvid Viaene: It’s a great honor to have you here. If listeners remember only one thing about the EU ETS — its origin story, its purpose — what should that one thing be?

Origins of the EU Emissions Trading System

Jos Delbeke: It started as a splendid economic idea. Economists wanted to contribute to climate policy and argued for economic instruments; there were many blueprints.

But having a blueprint is one thing. Implementing it in real life is another, because the world changes. Along the way, you have to make adjustments and adapt the system. You can’t have everything fully sketched out at the beginning. So the ETS developed gradually, which is why we had different phases.

Every five years, more or less, we reviewed the legislation—and that was very beneficial. Building a new element of climate policy took time to mature. Today we can say the system is in place and works fairly well. We have a solid price signal, and emissions are more than 50% lower today than when we started in 2005.

We’re now entering the next phase and a new discussion. With the war in Ukraine, moving away from gas as much as possible, big changes in energy, and an industry that still needs to decarbonize, the landscape for the ETS is changing again. That requires another review and rethink.

Arvid Viaene: Thanks for that. One thing this episode will show is that while there is a blueprint, there’s also gradual implementation and revision. People sometimes expect you can design everything from scratch ex ante—but that’s hard because of uncertainty.

Could you give us a broad overview of the different phases of the EU ETS?

Jos Delbeke: Getting started was the most difficult part. When people internationally ask me—Brazilians, Turks developing their own systems—my advice is: get started, and start with sectors where monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV) is easiest.

That was our important early choice: focus on the energy sector and manufacturing industry. Now, with ETS2, we’re moving into households, etc. But at the time we deliberately chose the big emitters, because tracking and trading emissions requires significant administration. You also need a robust compliance system. That was, and still is, demanding—so we began with energy and industry.

Another recurring challenge in the EU is competence: how far Member States let you go. We initially started with economic instruments and incentives, and first tried a tax—because that’s the obvious route. But taxation requires unanimity, which is very challenging in the EU.

From carbon tax ideas to cap-and-trade

After nearly a decade of trying a combined carbon and energy tax, we shifted thinking. Instead of defining the price, we defined the maximum quantity to be emitted—the cap. The cap declines over time and allows flexibility for operators.

That flexibility mattered because business had to come on board—and they weren’t spontaneously. But they disliked a tax. They were willing to try an economic instrument and incentives—anything but a tax. We could build on that engagement from businesses willing to act on climate. Industry cared deeply about cost‑effectiveness—reducing emissions at the lowest possible cost. The ETS was the perfect tool.

Political push: Commissioner Margot Wallström

We also had a good dynamic with Commissioner Margot Wallström, who immediately picked up the ETS. She was open to economic incentives and insisted we start the system while she was in office. So we set a firm timetable to launch in 2005.

That helped create momentum with businesses, NGOs, Member States and everyone else. We launched in 2005, before the Kyoto Protocol entered into force in 2008. That helped because of the uncertainty then. We described Phase 1 (2005–2008) as a pilot phase.

As a pilot, there was no banking of allowances from Phase 1 into Phase 2 (2008–2012)—the first Kyoto commitment period. That helped, because setting the cap required estimates, and Member States didn’t want to leave that entirely to the Commission. So that was a difficult exercise.

Building the Foundation: MRV and Compliance

We focused on MRV.(Note: Monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV)) You need companies to report emissions and a verification system so third parties can verify reports. Without trust in data, the market won’t function. So we were focusing on the essentials. On which elements did we have the most confidence.

Member States did most of the work and had a big say on the cap and allocation. Allocation was mostly free; there was no auctioning platform. Member States had an implicit concern to protect industry, creating an inherent tendency to inflate the cap.

Lessons from Phase 1: Overallocation of permits and need for better data

We were aware of that. What we didn’t foresee was that after the first year, over‑allocation was so clear that prices fell toward zero. That was a wake‑up call for businesses, Member States, and the Commission: when starting over in 2008, we needed much better data.

How did we get better data? By getting started. The MRV system established in Phase 1 became the perfect starting point for Phase 2. From 2008 onward we allowed banking because we had a much clearer picture of who emitted what. We had a great database—enviable compared with other environmental legislation at the time. It was that much better compared to other datasets at the time. So we used the pilot phase to set up the essentials. In Phase 2, the debate became more political—about the cap and the allocation process. Perhaps we can go into that later.

Arvid Viaene: One thing worth emphasizing: 2005 is twenty years ago now. IT wasn’t what it is today. It must have been a huge effort. It sounds like Phase 1 was used to get measurement and verification right so the rest could follow.

Jos Delbeke: Absolutely—that was the orientation of Phase 1. Phase 2 began real emission reductions. The largest reductions since 2008 have been in the power sector. Back then we had a lot of coal‑fired power generation. We gradually substituted coal with gas‑fired power generation. Fuel switching from coal to gas was supported by the carbon market and by decisions CEOs were making.

A psychological factor shouldn’t be underestimated: as soon as the ETS was agreed, CEOs knew they would have to pay a price for pollution. Nobody knew how high, but the fact of paying sunk in across boardrooms.

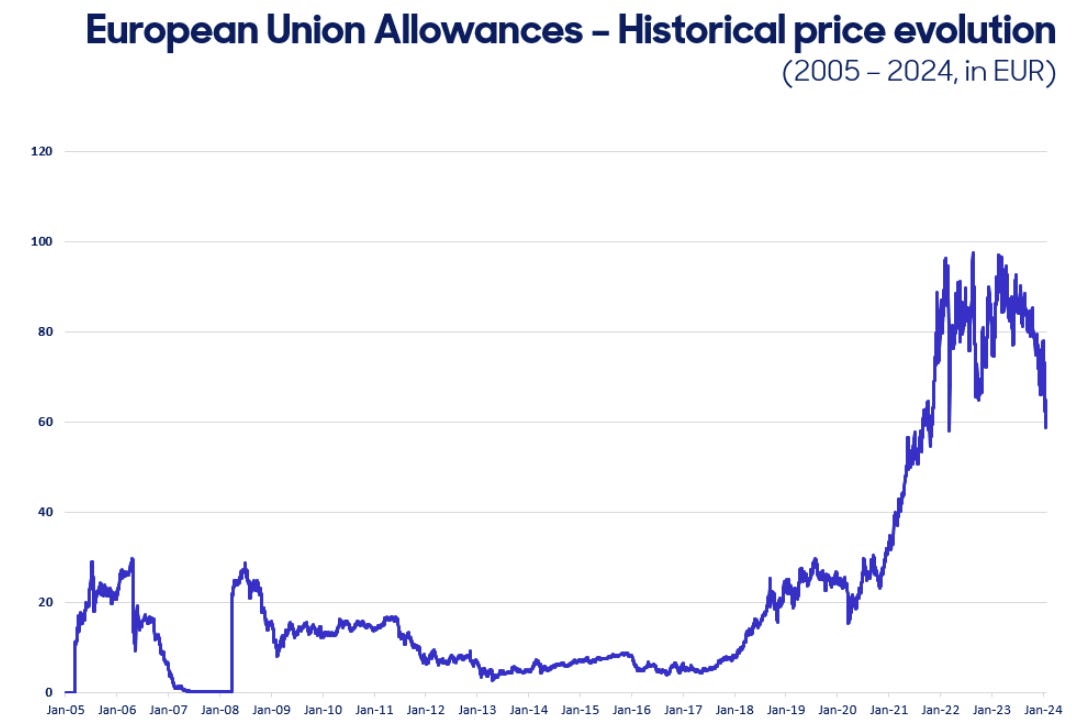

In the first period, prices were not bad—around €20–25—certainly better than later during the recession after the 2008 banking crisis.

That psychological element—you will have to pay for pollution—had an important impact. Companies, especially in energy, saw a way out: switch from coal to gas. When deciding on new power stations, invest in gas rather than coal. Europe’s reliance on gas was, in part, encouraged by the ETS because gas is less carbon‑intensive than coal.

Arvid Viaene: You’re describing CEOs becoming aware of the incentives, so they could plan and prepare.

Jos Delbeke: Exactly. Several companies began using an internal shadow carbon price for investment decisions. It was a guess where the ETS price would go, so they set their own benchmarks—€25 or €50 early on; later, many used €100 for internal planning. Expectations were factored into investments with lifetimes of 10–25 years.

Arvid Viaene: Let’s transition to 2008. There was the political discussion around reduction targets, and then the financial crisis hit. Could you elaborate?

Jos Delbeke: We had an important guiding framework: our Kyoto Protocol commitment for 2008–2012, which defined the EU’s overall effort. That overall effort was split between ETS‑covered sectors—industry and energy—and other sectors like households, heating and transport. In modeling, we carved out which part of the cap needed to be delivered by ETS sectors and which by Member States in non‑ETS sectors. That was easier in analysis than in politics.

Member States wanted a strong say in allocation rules, especially free allocation. In Phase 1, auctioning essentially didn’t exist—perhaps one or two percent of allocations where a Member State tried it.

During those years, criticism of the ETS grew, particularly concerning the power sector. The sector has minimal trade with non‑EU partners; it’s essentially European. Free allocation aimed to address competitiveness risks for trade‑exposed industries like steel, chemicals and cement—not power. The free allocation argument worked much more for the free market, but not for the power sector.

We observed that power producers were passing through the price of carbon allowances into electricity prices—even though they received most allowances for free. This led to a debate about windfall profits. The emerging consensus was that, in the next phase, auctioning should become the rule for the power sector.

That became the rule in Phase 3. Free allowances were limited to manufacturing. This was a major step forward, also because revenues could be used wisely. We created the Innovation Fund and Modernisation Fund, and most revenues returned to Member States. At that time, we couldn’t condition how Member States spent ETS revenues on climate purposes. They were keen to use revenues as they saw fit. Only later, in Phase 4, did a requirement arrive to use ETS revenues for climate policies—for innovation, home insulation, and more.

The real shift was moving the power sector away from free allocation to auctioning, and establishing common rules for free allocation in manufacturing. Through that process, we gradually Europeanized decision‑making for the ETS. Initially, Member States dominated. But auctioning largely escapes Member State discretion. We advocated for a common auctioning platform—eventually realized: the EEX in Leipzig conducts ETS allowance auctions. Member States were reassured they’d receive revenues without Commission interference, except for the innovation‑related funds. And that worked well. And that reassured Member States.

Harmonisation and a Single EU Carbon Market

Arvid Viaene: Switching from allocation (we can return to carbon leakage and CBAM later) to emission targets: as I understand it, in Phase 2 they were still set nationally, and in Phase 3 they became EU‑wide. Was that a gradual process? In Phase 1 there was over‑allocation and everyone was caught off‑guard by how much. What was the evolution from Phase 2 to Phase 3?

Jos Delbeke: The realization was that we had to implement our 2008–2012 Kyoto commitment to reduce emissions by a preset percentage—a common EU‑wide effort. We had to translate that into the ETS sectors versus those managed directly by Member States (households, transport, agriculture). The power and manufacturing sectors were increasingly viewed through an EU‑wide lens because we were opening markets—liberalizing electricity and building the internal market for goods and services.

These were the years of Jacques Delors and beyond, with the Single Market as the centerpiece of European construction. We brought that logic into the ETS, moving to EU‑wide coverage and a system that would gradually become fully harmonized—implemented by Member States, but harmonized.

This greatly improved cost‑effectiveness: on a wider scale you can chase the lowest‑cost reductions. So the wider the market, the more you get those benefits. Theory supported that. The UK had started debating a carbon market before the ETS, but the UK alone is a limited market compared to a large, liquid EU market. Denmark also attempted its own system, but it’s a small country relative to the EU market.

We were winning the argument for a single market for carbon allowances. That was creeping in gradually. Each time we tried to legislate it, it was easy to propose but hard to agree. In the end, we got there.

Oversupply After the Financial Crisis

Arvid Viaene: Let’s discuss the 2008 financial crisis. As I understand it, there was a drop in production and emissions, causing oversupply and downward pressure on prices. How was this experienced, and what steps did you take?

Jos Delbeke: There was a perception that prices were very low, and background grumbling about whether the ETS served its purpose at such levels. Two or three elements are worth adding. First, the industrial recession created an oversupply of allowances relative to the cap. Second, under the Kyoto Protocol, we had agreed that a fair amount of credits generated in developing countries could enter the EU. We did that expecting Russia, Australia, Canada, and the United States to participate in that international carbon credit market. In the end, they all pulled out, starting with the United States. And then those credits came en masse to Europe. So we had oversupply due to the recession, and on top of that, imports of carbon credits. Even with a low price, it was better to have a guaranteed price in the EU than nothing elsewhere. In the end, we imported about 1.6 billion carbon credits during the period the opening existed.

We acted on both elements. We asked the UN to tighten rules for credits because there were scams and irregularities—which they didn’t do, to my frustration. So we initiated the process to close our ETS market to credits from abroad. That debate continues today as to whether we should reopen to credits created under the Paris Agreement. That is another debate, I think we should do that. But at the time we needed to cut oversupply.

Stabilising the Market Price through the MSR

The second element—long in the making—was to put oversupply in a fridge, which we now call the Market Stability Reserve (MSR). We tried postponing some allowances that wouldn’t be auctioned, and similar steps, but only the MSR really did the trick.

The MSR defines a rule: when too many allowances come to market and aren’t absorbed, they go into the fridge and can come back later. A tool borrowed from financial markets, it worked fairly well. The night we reached agreement, prices began moving up from €5–6 immediately that night, to €25–30 in a couple of months. We left the low prices behind

European Green Deal and tightening expectations

Then came the European Green Deal, which strengthened expectations of a tighter cap. Prices rose from around €30 to €50, €60, €70, €80—with a record price of €100 in February 2023.

So the price recovery was due to closing the market to international credits, creating the MSR, and the Green Deal expectations. Those three elements explain today’s price levels. We also have a mild recession. Prices around €75–80 are a decent level given where we came from. A decent price works as a disincentive to pollute, and we see emissions going down. The incentive mechanism works. Some say the price should be higher; others complain it’s too high. I think today’s level is doing the job—that’s what matters most.

The Next 20 Years: Harder Abatement Ahead

Arvid Viaene: And by “doing the job,” you mean incentivizing companies to reduce emissions cost‑effectively within the EU pool.

Jos Delbeke: Absolutely. However, after 20 years of the ETS, the cheapest reductions have been realized. Over the next 20 years, the most expensive and difficult reductions lie ahead. That means we’ll need not only a relatively high carbon price, but also to avoid reaching climate targets simply by closing industry. We want industry to invest in decarbonized equipment. That’s the new challenge—captured in the Clean Industrial Deal—to accelerate and motivate decarbonized investment programs instead of importing more and closing activity.

Most reductions so far came from the power sector, with renewables coming in. The bigger task now is decarbonizing manufacturing—how to facilitate investments, deploy clean technology, and structure risk‑sharing and guarantees to enable investment decisions.

Governance Lessons for New ETS Designers

Arvid Viaene: Two follow‑ups. There’s a blueprint, then reality and surprises—lots of learning by doing. You’ve spoken with people in other regions. What lessons can others learn from Europe so they don’t have to experiment as much themselves?

Jos Delbeke: The most important—and most difficult—lesson is the need for good governance. You need solid MRV, and a strong central authority to set, decide and enforce the cap, with sanctions for cheating. When emissions equal money, there’s a risk of cheating—something we faced. Some allowances were stolen; operators were caught, jailed, and forced to repair the damage. That strengthened governance—for example, through a central registry held by the Commission to record ownership transfers accurately.

Good governance is essential, but it makes things complicated, which is why only strong governments have managed to implement ETSs.

China adapted our system to Chinese circumstances. Others are trying as well—Turkey is fairly advanced; Brazil and Indonesia are very advanced. There are always hurdles along the way. Establishing the system depends on good governance and a central authority that can impose rules and make it work.

Following governance is sound cap‑setting. Democracies must decide the rate of decline of the cap. Some want to go faster; others slower. That’s true in Europe—e.g., in current 2040 target discussions—and elsewhere. The cap needs to be clear to everyone. The payoff is reducing emissions at lowest cost while creating a business incentive for clean technologies. That’s the essence of 20 years of the European system.

New challenges for the EU ETS Future

Arvid Viaene: Final question. Prices are higher now and we’ve done the lowest‑cost options. Looking ahead, we have the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) and EU ETS 2—novel ideas the EU is pushing. Are lessons from past processes being incorporated, given cooperation with Member States, unexpected outcomes, and course corrections?

Jos Delbeke: Absolutely. International competition—particularly carbon leakage—will be crucial. From 1 January 2026, CBAM moves into real action. (Note: Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM)). It will be important to assess impacts, how it functions, and where to improve. This links to the carbon price. In the past we didn’t need CBAM because prices were much lower. Now prices are high and may rise as we pursue reductions higher on the cost curve. That raises liquidity and volatility questions.

We should consider the functioning of the Market Stability Reserve. It addresses overly liquid markets and too‑low prices. Perhaps we need to complement it for phases of insufficient liquidity and price spikes. The MSR merits a solid assessment: how well it worked and how it could be revised for a system tackling the remaining, more expensive reductions while navigating trade issues.

There’s the trade dimension: China exporting large volumes of clean technologies; the United States; and broader geopolitical changes. I mentioned gas availability from Russia—cheap Russian gas is off the table for Europe. Switching from coal to gas must be viewed in a completely different context now. So geopolitics—trade in energy and energy‑intensive commodities—will certainly be a consideration in the next ETS review.

Arvid Viaene: Jos, thank you so much for coming on. I really enjoyed this conversation and found it very insightful.

Jos Delbeke: You’re welcome. As you say, it’s a fascinating subject because the world around the ETS is constantly changing. That’s why I still follow developments closely and, here and there, try to inspire those doing the work with ideas and options for addressing various elements.

Arvid Viaene: This will definitely do that.